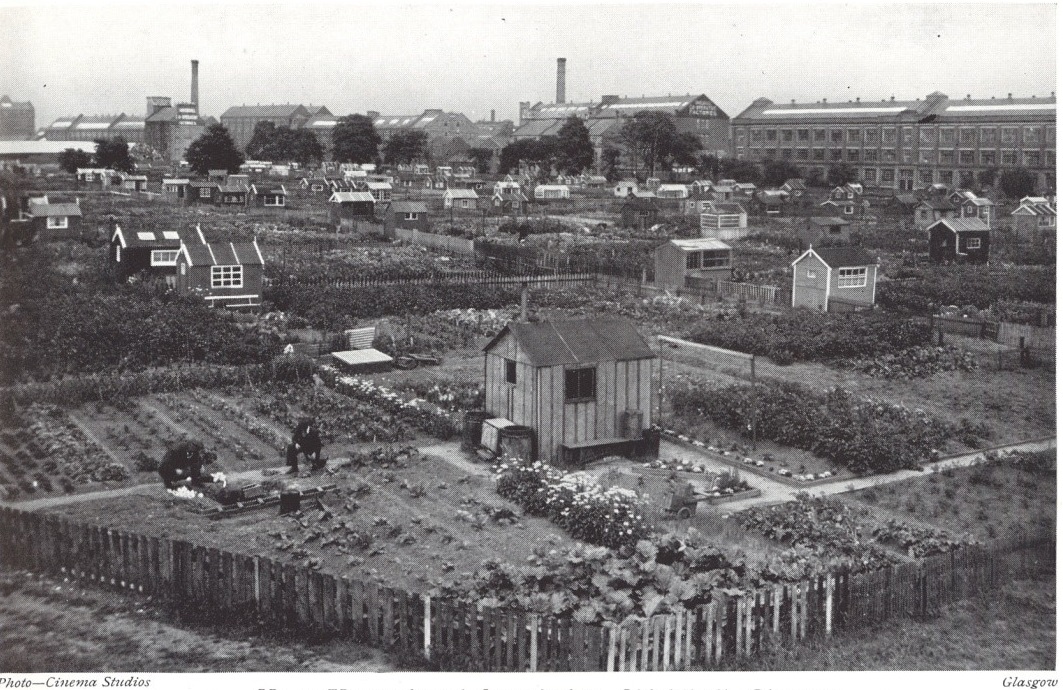

No. 3 Unemployed Association, Shieldhall, Glasgow. Credit: University of Glasgow Archive Services. The Papers of Victor Webb, Scottish Allotment Scheme for the Unemployed Annual Report 1935, pg. 5

Communal Gardening and Social Action in Scotland

by Hannah Baxter

Communal gardening has long been used for social action in Scotland. Perhaps the most famous example of this was when people worked together to ‘Dig for Victory!’ during the Second World War. I am working on a PhD on the history of allotments in Glasgow and in this blog I would like to share the story of a gardening scheme which has shaped the allotment movement here in the city.

In the late 1920s and 1930s Scotland was experiencing mass unemployment, the result of the closure of coal mines and a massive reduction in the ship-building industry on the Clyde following the restrictive peace treaty terms made after the First World War. The Society of Friends (also known as the Quakers) and the Scottish National Union of Allotment Holders (re-constituted as the Scottish Allotments and Gardens Society in 1946) came together to create a scheme to help the unemployed. They set up the Scottish Allotment Scheme for the Unemployed in 1932. This scheme worked to provide plots for unemployed men and women by both using existing sites and founding new sites especially for unemployed people, including the Garscube Allotments in Glasgow which are still inexistence today (although now they are for everyone!). As well as finding land, the scheme also offered grants to plotholders to cover tools, seeds, seed potatoes and manure. The aim was that plotholders would be able to produce food for their families but the Friends also believed that having something active to do (perhaps especially for people who had lost manual jobs) would keep the plotholders physically and mentally healthy. An allotment provided something very meaningful – it was not just something without purpose to simply fill time. Looking after a plot enabled the gardeners to take control over something – making their own decisions and taking responsibility – but crucially it did not leave them on their own. Working an allotment garden rather than a private garden forms a community that helps and inspires each other. This too must have been vital for those who had been used to working in industries which had previously formed their communities. In its first year, the Scottish Allotment Scheme for the Unemployed helped 2300 people across the country. In 1935 8153 people were supported by the scheme, but as plots were of a size to feed a family of four it could be said that 32,000 people were assisted by the scheme.

One thing that has struck me in looking at the unemployment scheme’s photos from the 1930s is that the Friends favoured open plan sites. If there are hedges these are quite low. Of course, this could be because they have not matured yet! But where there are fences in evidence these too are low – high enough to be a boundary but low enough to have a conversation with a neighbour. Individual plots provided the sense of ownership the Friends promoted for building independence but the openness of the sites meant that vulnerable people did not become cut off and alone.

Huts, too, were used to bring plotholders together. In 1934 the English and Welsh sister scheme published a booklet containing detailed plans for huts, greenhouses and shelters for animals. This was also used in Scotland and the unemployment scheme offered grants to cover building materials for communal huts on the condition that the plotholders constructed the huts themselves. In 1936 thirty-seven communal huts were provided across Scotland and the scheme’s annual report stated that they were of ‘great benefit to the plot-holders, many of whom live a considerable distance from their plots’. As well as being a shelter from bad weather and a storage place for tools, plotholders were also encouraged to hold social events in these huts such as dances and whist drives to bring families together.

Often I feel history is used in public to remember terrible, even evil, events and ‘remind’ ourselves not to do them again. Whilst this is a genuine way for history to be important in society, I also think history can be used to remember events and say ‘That was wonderful! What can we learn from that now? Can we use it today?’ Whilst learning about the Scottish Allotment Scheme for the Unemployed I have been struck by how similar the scheme was to the grassroots schemes at allotments and community gardens in Glasgow now, helping people as Robert, John, Deirdre and Andrew described in their last blog. To me, the unemployment scheme can be used as an encouragement that gardening can empower people at difficult times in their lives; it provides joyful activity but also hard work; it provides time to be quiet and peaceful but also friends and liveliness and gives us hope and delight in seeing things grow.

The information used for this blog comes from the Papers of Victor Webb which are held at the University of Glasgow Archive Services. Victor Webb was a plotholder and a Friend in Edinburgh who was greatly involved in the Scottish Allotments Scheme for the Unemployed as well as campaigns to protect allotments from the 1950s to 1990s. He collected reports, minutes, letters and newspaper clippings which have formed the basis of my work – I am profoundly grateful to him for being a such a careful hoarder!

The author, Hannah Baxter, is based at the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences at the University of Glasgow.